Free Will and Determinism: The Landscape

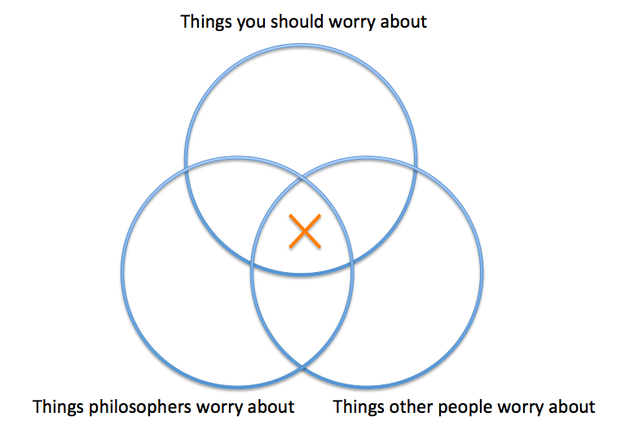

The problem of free will is something philosophers and non-philosophers worry about -- and should worry about. Everyone with a will has an interest in whether that will is free.

As conscious beings, we humans are able to make decisions, reflect on the way we make decisions, reflect on the way we reflect on the way we make decisions, and so on. We have the amazing capacity to change our long-term behavior and influence our desires so that our decisions more fully support our vision for the lives we want to lead. We can override our most powerful basic desires. We can fast, abstain from sex, and even sacrifice our own lives. When we are deciding what to do, it always seems to us that there are many paths we can take. Descartes held that as far as pure will goes, humans are equal to God. I think that's very cool.

Here's 100% of my ability to will, 0% of my infinite power, wisdom, and goodness. Good luck.

At the same time, we are part of the natural order. Our brains are the most complicated physical structure in the universe that we know about, but they are similar in kind to other mammalian brains. No physicist has ever recorded a violation of natural law within human skulls, and it would be very strange if the laws of nature ceased to function in this very parochial location. (Of course, many people believe that humans have souls which are not part of the natural order and which were created by God so that we would have the ability to choose freely. Most philosophers these days do not think there are souls. This will be explained in a future entry.)

In particular, it would seem that our decision-making process is part of the natural order. Our ability to reflect on our various options, decide what to do, override some of our desires, and improve ourselves is a skill that cognitive scientists and neuroscientists can study, just as we study parrots' ability to vocally mimic. Our hearts are mechanisms, and are determined to act in the ways they do because of the stimuli they receive. Our brains are mechanisms, too. Why shouldn't we think they are determined to act in the ways they do because of the stimuli they receive?

An obvious difference between our hearts and our brains is that it is much easier to predict what our hearts will do. Our brains are much more complicated. But just because it is sometimes hard to predict what a person's brain will do, does not mean that the brain is not a mechanism which works just as deterministically as a heart.

If our brains do function deterministically, that means that at every moment, the circumstances we are in plus the laws of nature necessitate our actions. This seems to undermine the idea that we have a genuine choice among a variety of options, and the idea that we should be held responsible for the actions we perform.

There are three classic philosophical responses to the conflict between thinking of ourselves as part of the natural order and our conscious experience of ourselves as having an open-ended future.

Hard determinism: all human actions are causally determined, and none are free.

Hard determinism is called "hard," presumably, because it is tough-minded: it fully acknowledges the reality of our lack of freedom and responsibility.

Libertarianism: some human actions are free and not causally determined.

This is not to be confused with the political doctrine. Libertarians think that humans have the ability to act outside of the natural order.

Even though there is a sense in which hard determinists and libertarians are fundamentally opposed, there is also a fundamental sense in which they agree. They are both incompatibilists, holding that free actions cannot be causally determined. Accordingly, both are opposed to the third classic philosophical response:

Compatibilism: all human actions are causally determined, yet some are free.

Compatibilism is also called soft determinism, presumably because it tries to avoid the tough-minded conclusion of hard determinists. When I teach the free will debate, students are often most perplexed by compatibilism. How could an action be causally deterimined and yet free? It turns out that compatibilism can be even more perplexing, because many compatibilists hold that freedom actually requires determinism.

In the next posts, I will make some general observations about freedom before I say more about these three views.

Copyright 2019 by Sam Ruhmkorff