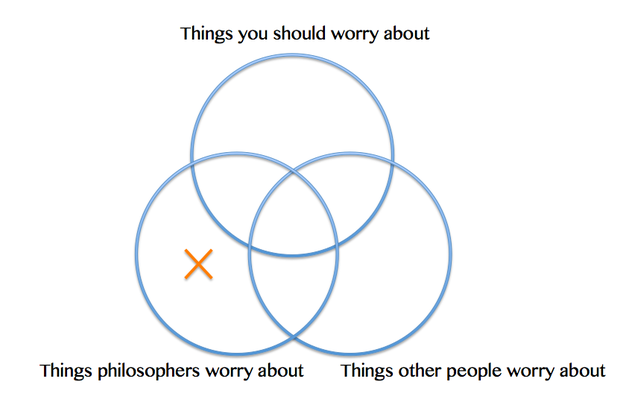

Grade B

In the last post I wrote about the problem of figuring out whether statements like:

Sherlock Holmes lives at 221B Baker Street

are true or false. This puts us squarely here:

Perhaps you are thinking we want to say both things. We want to say that Sherlock Holmes lives at 221B; and at the same time, we want to say that he doesn't because he doesn't even exist. If you are thinking this, you are in the company of many philosophers who have thought it, too. There are several ways philosophers have tried to have their cake and eat it too. Today I want to write about the wildest. It stems from reflection on the Holmes statement:

Sherlock Holmes does not exist.

Excuse me...

This seems like a meaningful thing to say. Meaningful things are about something. But what is the Holmes statement about? It can't be about Sherlock Holmes -- it says he doesn't exist! It looks like it is about nothing. Then it can't be distinguished from:

Elizabeth Bennett does not exist.

The Holmes and Bennett statements seem to be saying different things. You could believe one without believing the other -- say, if you were unsure about whether Holmes was a fictional character. Yet these statements seem to be about exactly the same thing: nothing. We are squarely in the realm of metaphysics and ontology.

A Note on Metaphysics and Ontology

Metaphysics is the study of the most basic constituents of the universe: things, properties, people, possibilities, and causes.

After telling someone that I taught, among other things, metaphysics, I was told: "Be careful -- that is the way to the devil." She was thinking of the "Metaphysical Studies" section in Barnes & Noble, which deals with astral projection and other New Age ideas. I forget whether I tried to reassure her by telling her that no, I teach metaphysics; if I did so, I forget whether she was reassured. So, if you are interested in metaphysics, be careful whom you tell!

Ontology is usually said to be the study of what exists. Whether or not God exists is an ontological question. But this isn't quite right. If ontology were the study of what exists, people who track everyday objects would count as ontologists.

The train is just behind those ontologists.

We aren't doing ontology every time we discover a new dust bunny under the bed. So instead I said ontology is the study of what kinds of things exist. Do you think that only matter exists? What about numbers? Angels? These are proper ontological questions. But perhaps this definition isn't quite right, either, because it means that biologists who discover new species are ontologists as well as biologists. It turns out that it is hard to define even the most basic terms in philosophy.

The wild idea -- associated with Meinong and Parsons -- is that Sherlock Holmes enjoys a kind of being.

That's better.

Anything we have a concept of -- or, on some versions, anything we could have a concept of -- subsists. I think of subsistence as Grade B being. You don't get to roam the world and eat real food, but at least you can be talked about.

Grade A being is full-fledged existence. That's what we have that Sherlock doesn't. We subsist like him, because people have concepts of us. We also exist, because we can act in the world.

Many people have problems with Grade B existence. Meinong is positing a whole new kind of being just to explain the way we talk about stories. In general, we should be reluctant to say that things are real unless we have a very good reason.

Copyright 2019 by Sam Ruhmkorff